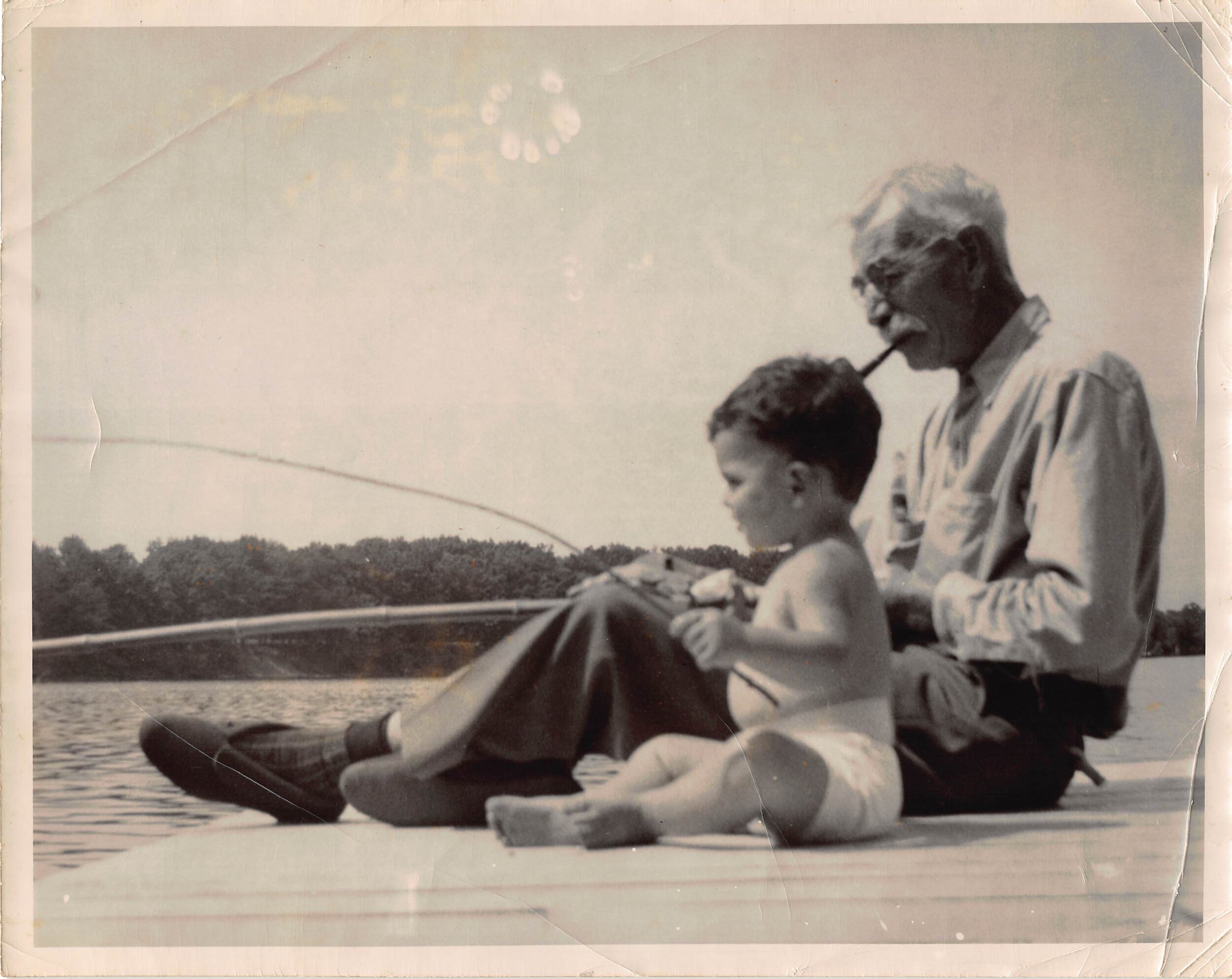

In the photo above, the diapered little boy delightedly “fishing” on the dock is me.

The sweet, attentive older man smoking a pipe and fishing—but focused entirely on me—is “Dad” Wright.

My father took this photo so my mother could enjoy again and again that Dad Wright and I had not only met but had enjoyed a sunny day fishing together when I was very young.

Dad Wright: the Only “Father” Who Stayed in Her Life.

The full name of “Dad” Wright was John Russell Wright. But to my mother, whose parents divorced before she was less than one year old, he was a godsend, the man from her rural community in Michigan who became her surrogate father, her “Dad.”

Dad Wright adored her, helped her, believed in her, and nurtured her through the rocky years when she not only lacked a father but was part of a family ostracized for two “unforgivable” events: the earlier suicide of her alcoholic grandfather and the more recent divorce of her parents.

What to Name Her Second Son?

When my mother was pregnant with my younger brother, Dad Wright asked for something—the first request he had ever made of her in his long years of loving and supporting her.

Typically, he didn’t make the request directly to my mother, but to my father, who had grown to know and love Dad Wright, too. He said:

Paul, if this baby is a boy, I would love it if Virginia named him after me.

Now, I would never expect you to saddle a boy with the name, “John,” but maybe you could use my middle name, “Russell”?

The Boy’s Name Is…

My mother gave birth some months later to my younger brother. In the hospital, she was asked to fill out a form with the name of her new child. She wrote,

Bradley Darrell Lipman

My dad asked her, “Why didn’t you name him ‘Russell’?”

She replied, “Well, Douglas is "Douglas Brian": his initials are ‘DB’. I thought it would be nice to have our new son’s initials as the reverse, ‘BD’ for ‘Bradley Darrell’.”

My father reminded her of what Dad Wright had asked, but she wouldn’t budge.

My Father Submits the Birth Certificate

My father took the birth certificate to the nurse’s desk to file it. But when he arrived at the desk, he changed the certificate to read,

BradleyDarrellRussell Lipman

I heard my dad tell this story to me and my mother when I was an adult. I looked at my mother, expecting her to be angry.

But she was smiling. She seemed glad, in the end, to have granted the one request of the first man who had fully taken her into his heart.

Do We Do The Same Thing With Our Stories?

In nearly every story I develop, there comes a moment when I become fascinated with a “brilliant” idea. It might be a clever phrase, a song I long to insert in the story, or a scene that moves me or seems masterful.

Some of these ideas are clever, even moving. But the ones I'm talking about here all turn out to have one major problem: they distract listeners from the central meaning that the story has for me.

In other words, I get fascinated with my own version of “DB & BD.” In the flux of story-adjustment, I lose sight of what really matters—of who or what the story is meant to portray, convey, or honor.

I lose sight of the central image of, say, kindness and love.

There is no cleverness that can be stronger than such an image! And it’s the job of every storyteller to make sure that the “Most Important Thing” in a story (whether it’s an experience, an image, or a theme) always gets pride of place.

Building? Or Growing?

The story-building process can tempt us to look for pretty "bricks" (like “BD" vs. "DB”) and get so attached to them that they crowd the story’s “most important thing”—for us as the teller—out of the spotlight.

Whenever this imbalance happens, the story becomes muddier and less compelling.

That’s why it’s important to learn the more advanced techniques of story-growing. They help you:

Decide and remember what’s most important, and then

Follow it through in every aspect of the story.

It’s up to you. Do you want to create a “BD vs DB” (something clever but not important) or a “Bradley Russell” (something that focuses on an aspect of our humanity)?