Why don't storytellers (and even many story-writers) make better plots?

Here are a few "plot confusions" that might contribute to the problem:

For many storytellers, plots don't always seem as interesting as characters, places, and points of view—so we aren't as motivated to understand their essence and ways to help them grow;

Indeed, plots often seem abstract and mathematical (they aren't really), whereas most storytellers care more about emotions and experiences. So we don't enjoy good relationships with the world of plot; and

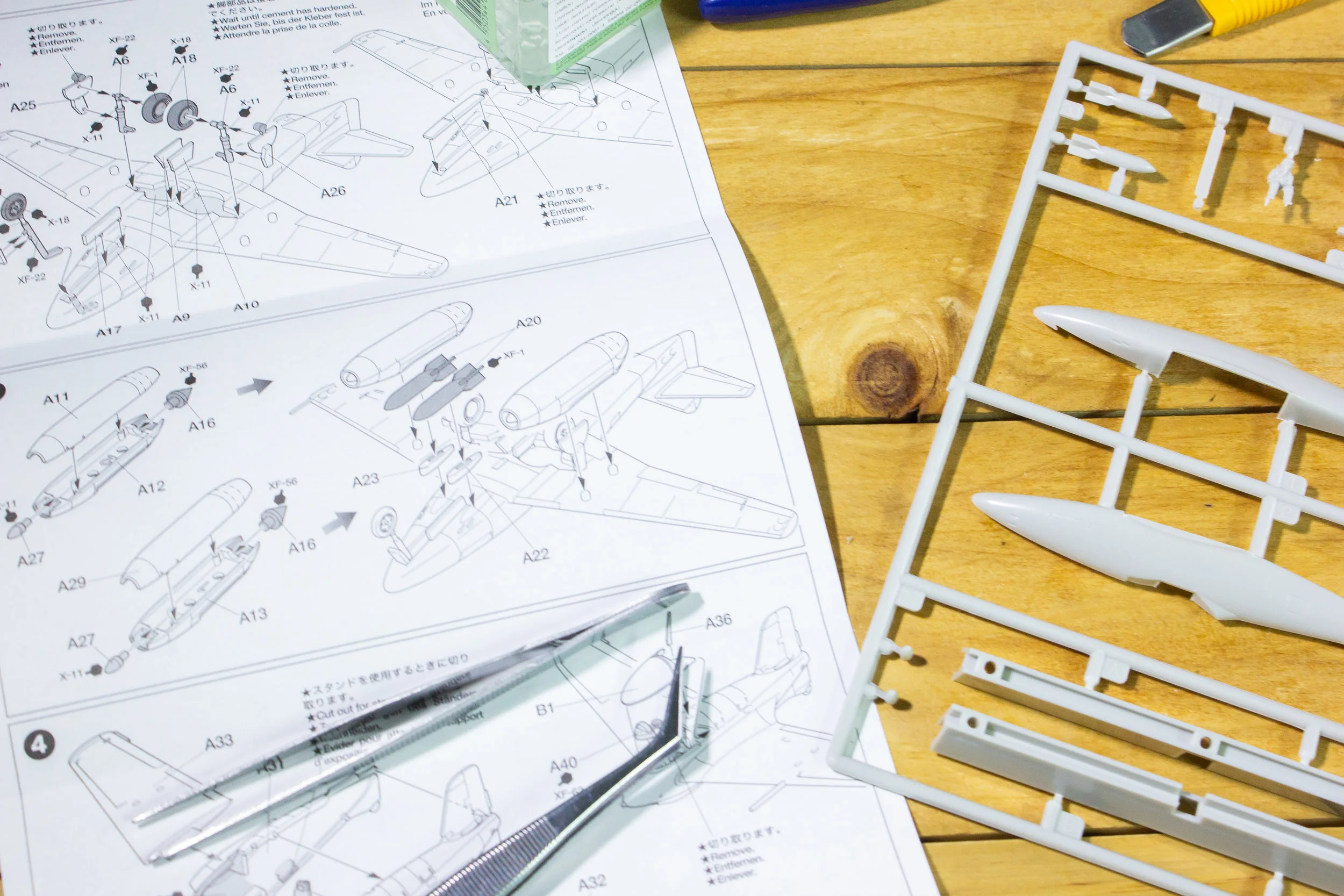

We've been told to "assemble" plots (examples range from misunderstandings of Aristotle to the Hero's Journey, Freytag's pyramid—and many more "plot formulas"!)—so plots don't seem as "artistic" as the other elements of story.

In truth, plot is intimately interwoven with characters, the physical world, and character emotions.

So why do we believe those misleading falsehoods and half-truths?